Post Author

A decade of five-star work, gone in a click: How algorithms are quietly ending gig workers’ livelihoods.

- The Numbers Tell Us A Brutal Story

- Let’s Call It What It Is: Getting Fired

- The Robot Boss Problem

- The Financial Devastation Nobody Talks About

- The Wild Patchwork of Protection

- Seattle: What Real Protection Looks Like

- Washington State: The First Statewide Model

- New York City: A Victory That Just Happened

- Minnesota: A Hard-Fought Compromise

- Colorado: Transparency, at Least

- Massachusetts: Settlement, Not Law

- California: The Prop 22 Problem

- Oregon: The Fight Happening Right Now

- Everywhere Else: The Void

- Meanwhile, in the Rest of the World

- What You Can Actually Do

- The Bigger Picture

Twenty-six thousand trips. That’s how many rides Ahmed Alshamanie had completed for Uber when he testified before the Oregon state legislature. He’d been driving since 2014. His rating was 4.97 out of 5 stars. Uber had literally featured him on their website as an All-Star Driver, the kind of face a company puts forward when they want you to feel good about using their service.

And then, one day, his account was deactivated. No warning. No real explanation. No appeal that went anywhere. Just… gone.

I keep thinking about that number. Twenty-six thousand trips. That’s picking people up at 3 AM from the airport. That’s driving someone to their job interview, their chemo appointment, their kid’s soccer game. That’s a decade of showing up, over and over, building what you thought was a career. All of it erased with a notification on your phone.

And here’s the part that makes my stomach turn: Ahmed isn’t even unusual.

The Numbers Tell Us A Brutal Story

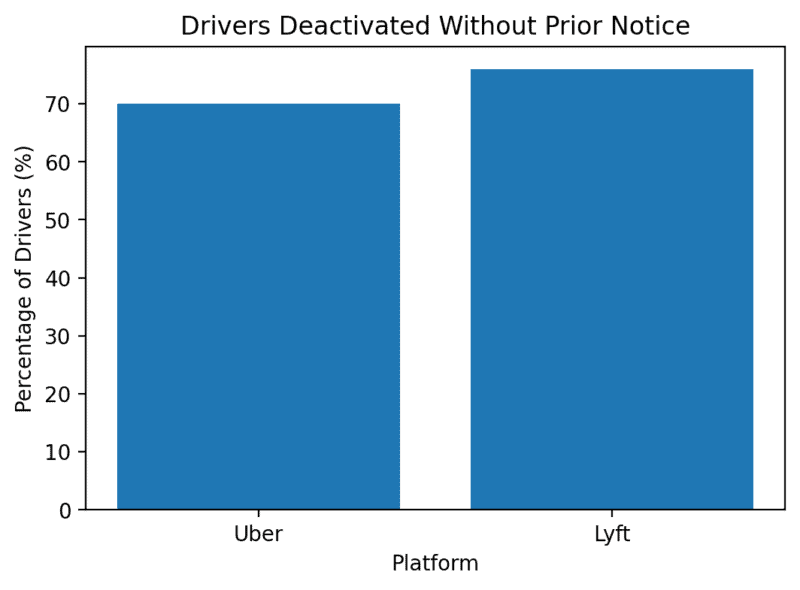

A report released in October 2025 by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) surveyed New York City drivers who’d been kicked off Uber and Lyft.

The findings are stark: 70% of drivers deactivated by Uber and 76% of those deactivated by Lyft received no prior notice whatsoever. They woke up, opened the app, and discovered their income had vanished.

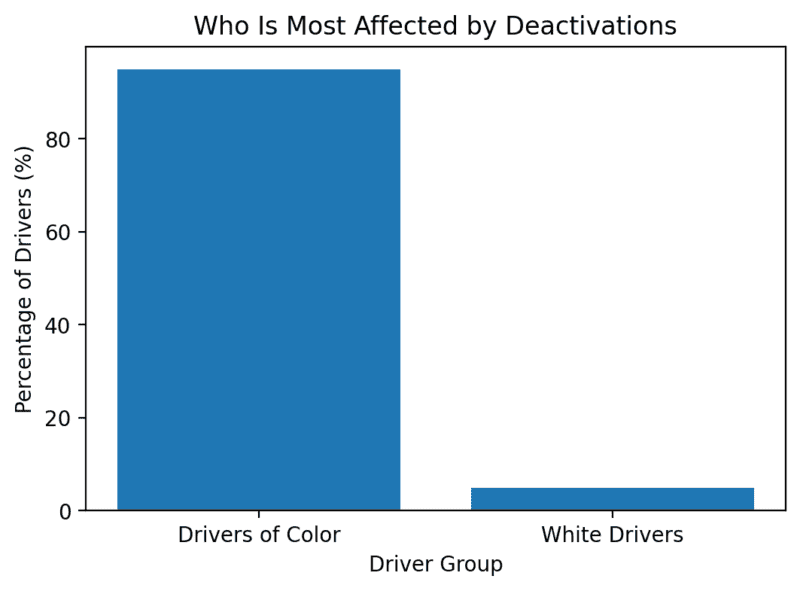

And there’s a pattern here that’s hard to ignore. Ninety-five percent of the deactivated drivers in that survey identified as people of color. Nearly all of them tried to appeal. More than 90% remained permanently locked out.

“Behind every deactivation is a human being,” Elizabeth Koo, interim director of AALDEF’s Economic Justice for Workers program, told Documented. “A parent, a provider, a New Yorker, suddenly cut off from income with no explanation and no recourse.”

These numbers echo what the Asian Law Caucus and Rideshare Drivers United found in California back in 2023. Their survey of 810 Uber and Lyft drivers revealed that two-thirds had experienced deactivation, temporary or permanent. Drivers of color and immigrants were disproportionately affected. The average deactivated driver had been on the platform for four and a half years.

Four and a half years! Think about that! This can’t be a side hustle. That’s a relationship.

Let’s Call It What It Is: Getting Fired

“Deactivation” is one of those corporate euphemisms designed to make something brutal sound technical. It’s like calling a layoff a “workforce optimization event.” What it actually means is: you’re fired, but we don’t have to call it that because you’re not technically our employee.

One day, you can accept rides or deliveries. And the next day, the app just… stops working for you. The reasons when they’re given at all range from failed background checks to too many customer complaints to vague “safety concerns.” Or sometimes, maddeningly, no reason at all.

I spent some time on the RideGuru forums reading drivers’ stories. One described getting this message from Uber: “During a recent review, we noted that your account is associated with multiple reports of safety concerns.” That was it. No specifics. No dates. No names. No opportunity to defend himself against whatever he was supposedly accused of.

“In my mind I think someone at Uber decided to get rid of some drivers in this area and fired me and used ‘safety concerns’ as a reason,” he wrote. “I don’t believe this had anything to do with safety concerns.”

Maybe that sounds paranoid. But consider the incentives these companies operate under. More drivers means shorter wait times for customers. More drivers means the algorithm can offer lower prices. And if one driver causes any sort of problem, real or imagined, the easiest thing to do is just remove them. There are always more where that came from.

“It’s cruel, man,” a driver named Jordan told the Los Angeles Times. “It’s almost like Uber sees their drivers like a piece of equipment or a gadget or something, and they can just flip a switch and turn you off.”

The Robot Boss Problem

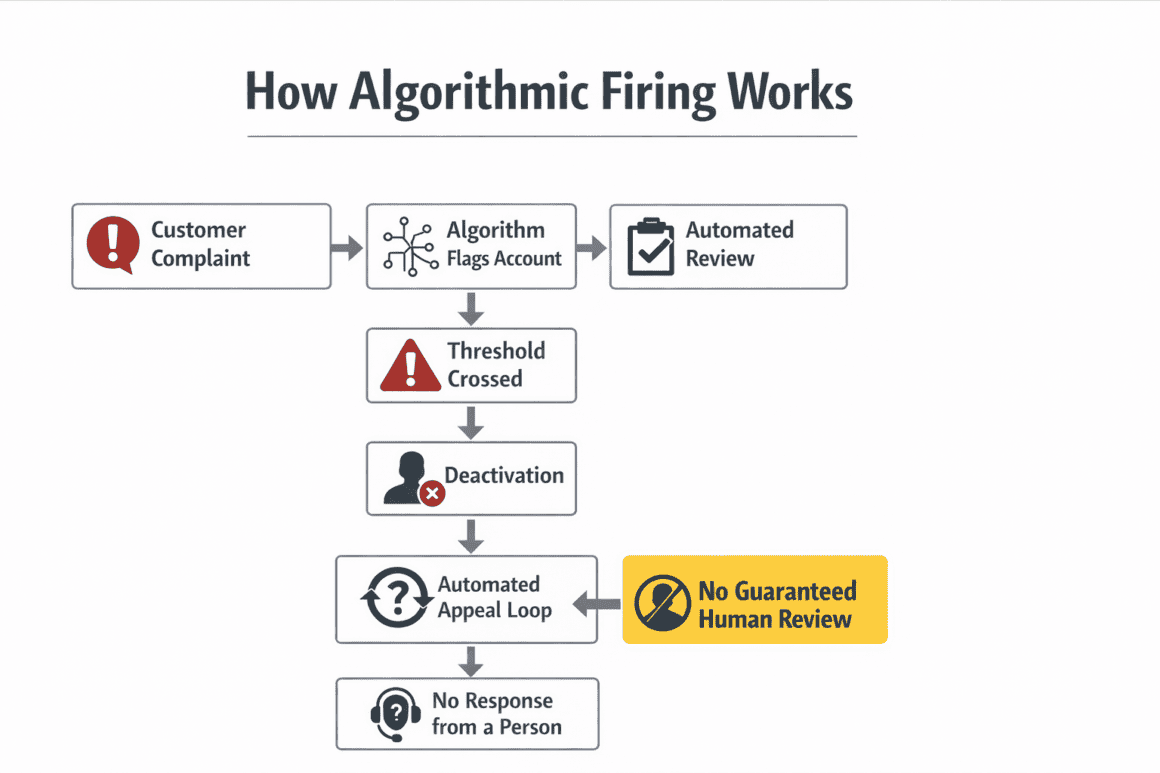

Here’s where things get dystopian. The decisions about who stays and who goes are increasingly made by algorithms. Automated systems flag “irregular behavior.” Customer complaints trigger automatic reviews. Rating drops below a certain threshold? The system might just… decide you’re done.

And when something goes wrong, drivers struggle to reach a human being who can actually help them. They get trapped in automated response loops, directed to FAQ pages, and told their appeal is “under review” indefinitely.

“There’s no worse feeling in the world,” said Nathaniel Hudson-Hartman, a rideshare driver and organizer with Drivers Union Oregon, in testimony to state legislators, “when you go out of your way to give people safe rides and to be of service to your community, to know that your job can be taken away by an algorithm.”

The Financial Devastation Nobody Talks About

I want to linger on the financial consequences, because I think they get lost in the policy debates.

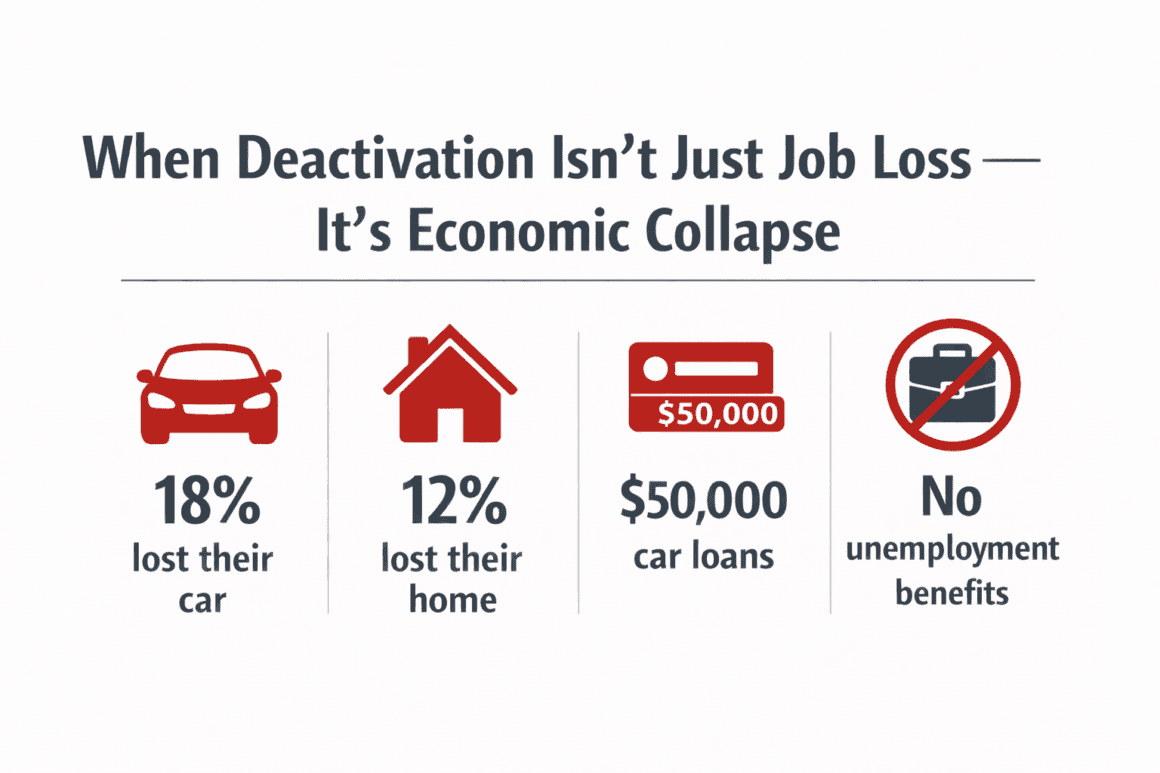

In the AALDEF survey, 81% of drivers said driving for Uber and Lyft was their main source of income. Not a side hustle. Not beer money. Their main income. And when they got deactivated, the fallout was severe: 18% lost their car. 12% lost their homes.

Here’s the part that really gets me: these drivers don’t just lose their income. They often have thousands of dollars in car loans. Loans they took out specifically to do this work. According to testimony at an AALDEF press event, New York Taxi Workers Alliance member Saif Aiza took out a $50,000 loan to finance his car for Uber. His monthly payments exceed $600. When he was deactivated, those payments didn’t stop. Now he’s filing for bankruptcy.

“After Uber deactivated me, I went to the Uber hub, I went to the Uber-funded Independent Drivers Guild,” Aiza said. “Neither would help me. Uber representatives told me that since I was a highly rated driver with more than 12,000 trips, I would get back into the app without any problems.”

And here’s what makes this different from getting fired from a regular job. Independent contractors, which is how Uber and Lyft classify their drivers, don’t qualify for unemployment insurance in most states. They don’t have severance. They have no wrongful termination protections. The traditional employment law doesn’t apply to them.

So when the National Employment Law Project says drivers “live under the constant threat of being ‘deactivated’,” as they wrote in a recent analysis, they’re not exaggerating. The threat is real, and for most workers in most places, there’s nothing they can do about it.

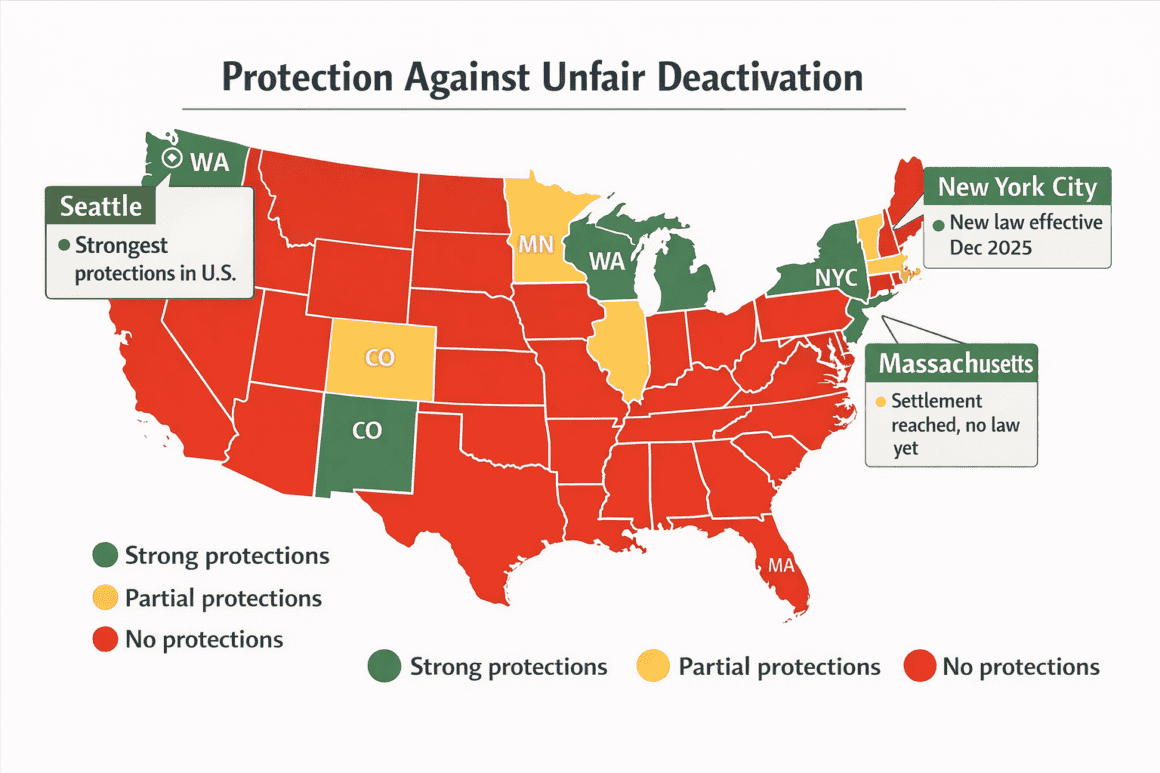

The Wild Patchwork of Protection

So I spent weeks mapping this out. Calling union organizers. Reading legislation. Pulling up forum posts from drivers who’d been through it. And what emerged was a picture of wildly uneven protection, depending entirely on geography.

If you drive in Seattle, you have real rights. If you drive in Dallas, you have almost none. Same job. Same companies. Completely different legal reality.

Let me walk through what exists.

Seattle: What Real Protection Looks Like

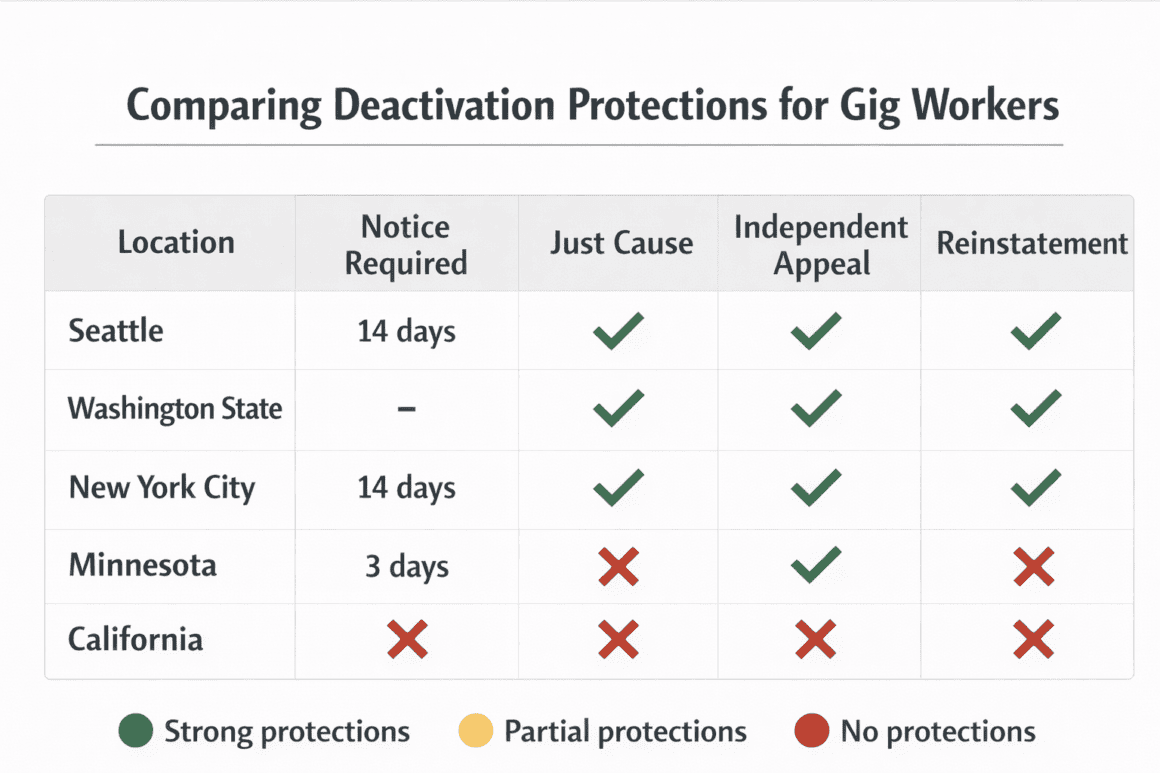

Seattle has the strongest deactivation protections in the country. Full stop. The App-Based Worker Deactivation Rights Ordinance went into effect on January 1, 2025, and it covers app-based workers, including delivery drivers and shoppers.

Here’s what it requires: Companies must give workers 14 days’ written notice before deactivation. The notice has to include the specific reason, the policy violated, and the date and time of the alleged violation. Companies must conduct a “fair and objective investigation” before deactivating anyone. They have to apply their policies consistently, no more arbitrary enforcement. And workers get access to records substantiating the deactivation, so they can actually see what they’re accused of.

There are also things companies explicitly can’t deactivate you for: Rejecting offers. Being unavailable. Exercising your legal rights. Speaking publicly about working conditions.

Starting in June 2027, the Office of Labor Standards will be able to investigate whether deactivations were for “permissible reasons.” Unlawful deactivations can result in reinstatement and back pay.

“Seattle is now the best city in the nation to do gig work,” the Fair Work Center declared, “and we’re showing the rest of the country what’s possible when workers organize for what we need and deserve.”

There’s an exception for “egregious misconduct” like harassment or robbery, where companies can deactivate immediately. That makes sense. But the default is: you can’t just fire someone without explaining why. Which, when you think about it, shouldn’t be a radical concept.

Washington State: The First Statewide Model

Washington was the first state to pass comprehensive protections for rideshare drivers. ESHB 2076, signed in March 2022 and effective January 2023, established a just cause standard for deactivations. Meaning: companies need a good reason to fire you. Revolutionary, I know.

The law also created a Driver Resource Center, operated by the Drivers Union, which represents drivers in deactivation appeals. It’s funded by a 15-cent fee on every trip. And it provides what the law calls “culturally competent driver representation services”, important given how heavily immigrant the workforce is.

“When it comes to protection against unfair terminations, we’ve achieved a just cause standard for terminations of Uber and Lyft drivers in Washington,” Peter Harwin of the Teamsters Local 117 told Protocol when the law passed, “which is a higher protection than people in an employer-employee relationship have in the state.”

Worth noting: this only covers rideshare drivers. If you deliver food for DoorDash in Tacoma, you’re not covered. But it’s still the model that other states are looking at when they think about what’s possible.

New York City: A Victory That Just Happened

On December 18, 2025, the New York City Council passed Intro 276, ending the threat of unfair deactivations for nearly 100,000 app-based drivers in the city. It passed 40 in favor, 7 against, and 1 abstention.

“Intro 276 sets the strongest standard for just cause protections for Uber and Lyft drivers in the country,” said Bhairavi Desai, Executive Director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance. “The passage of this historic bill means that drivers, who go into debt just to work, will no longer have to worry about going to sleep after a grueling day on the road only to wake and find they have been unfairly deactivated, left with no income overnight at the click of a button.”

The bill puts the burden of proof on companies, not drivers. It requires 14 days’ notice. It creates an independent appeals process not controlled by Uber or Lyft. And crucially, it allows drivers who were deactivated in the past to petition for reinstatement. A recognition that injustice doesn’t just disappear because time has passed.

Before this passed, NYC had a messy system. TLC-licensed drivers could appeal deactivations through the Independent Drivers Guild. But the IDG is partly funded by Uber, which made a lot of drivers understandably suspicious. The fox was guarding the henhouse.

“The fundamental problem here is that there is no existing law that says the company has to show any proof of wrongdoing before deactivation,” City Council Member Shekar Krishnan said during a hearing. “Right now, Uber is the judge, jury, and prosecutor against drivers. They are guilty before they are proven innocent.”

That changes now.

Minnesota: A Hard-Fought Compromise

Minnesota passed statewide rideshare driver protections on the final day of its 2024 legislative session, with the minimum pay provisions taking effect December 1, 2024. The law requires 3 days’ written notice before deactivation and gives drivers the right to appeal.

It also bans discrimination in deactivation based on race, national origin, religion, sex, disability, sexual orientation, or gender identity. And it prohibits mandatory arbitration. Meaning drivers can actually sue if they’re wronged, rather than being forced into a company-friendly private process.

This came after a bruising fight. Minneapolis had passed its own ordinance with higher pay rates, and Uber and Lyft responded by threatening to leave the state entirely. The final deal preempted the city ordinance but established statewide protections, a compromise that left nobody fully satisfied but gave drivers something real.

“This has been about fair wages, fair treatment, and protecting workers,” said Rep. Hodan Hassan, the bill’s author. “These are immigrants, new Americans. These are low-income people. These are Black and brown people… who want to achieve the American Dream.”

Three days’ notice is shorter than Seattle’s 14. There’s no just cause requirement. But it’s something, and sometimes something is what you build on.

Colorado: Transparency, at Least

Colorado passed two bills in 2024: SB24-075 covers transportation network companies like Uber and Lyft, while HB24-1129 covers delivery companies like DoorDash and took full effect in January 2025.

The laws don’t establish a just cause standard. That was in an earlier version, but got stripped out after company pushback. A reminder that even modest reforms face fierce opposition. What they do require is transparency: companies must clearly disclose their deactivation policies, explain the grounds for termination, and communicate how to request a “reconsideration meeting.”

“The Colorado legislation doesn’t fix all of this,” Jacobin noted, “but it does provide drivers in the state with greater recourse and more protections.”

Drivers can file civil suits for violations. The Division of Labor Standards can impose fines and even require companies to rehire wrongly terminated drivers. It’s nothing. It’s also not enough.

Massachusetts: Settlement, Not Law

Massachusetts is complicated. In June 2024, Attorney General Andrea Campbell reached a $175 million settlement with Uber and Lyft. The companies agreed to provide a “deactivation appeals process” and anti-retaliation provisions.

But here’s the thing: this is a settlement, not a law. It’s not codified in statute. The details of the appeals process are unclear. And worker advocates were frustrated that the settlement dropped the AG’s lawsuit alleging the companies were misclassifying drivers as independent contractors, the core legal question that underpins this entire fight.

“We will bring drivers together to make sure that reimbursements are paid out on a fair basis, and that the deactivation review process has meaningful enforcement powers to protect drivers from unfair deactivations,” Massachusetts Drivers United wrote in response.

On the plus side, Massachusetts voters passed Question 3 in November 2024, which allows drivers to form a union and bargain collectively. That could potentially lead to stronger deactivation protections through negotiation. We’ll see.

California: The Prop 22 Problem

California is, weirdly, both the birthplace of the gig economy and a place where gig workers have remarkably few protections. The irony would be funny if it weren’t so grim.

In 2019, the state passed AB5, which would have made most gig workers employees with full labor protections. In 2020, Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart spent over $200 million. The most expensive ballot measure campaign in American history was to pass Proposition 22, which exempted them from AB5. In July 2024, the California Supreme Court upheld Prop 22.

And the result?

California gig workers get some benefits, such as a health care subsidy and occupational accident insurance. But they get no deactivation protections. No just cause requirement. No meaningful appeal rights beyond what the companies voluntarily provide.

And there’s an enforcement gap. A CalMatters investigation in September 2024 found that “no one is actually ensuring” Prop 22 benefits are provided. The Industrial Relations Department says it doesn’t have jurisdiction. The AG’s office was noncommittal. It’s a law with no cop on the beat.

“The hunger games continue,” said Sergio Avedian, a rideshare driver and contributor at The Rideshare Guy, when asked about the Supreme Court ruling. “It means only a small percentage of drivers receive Prop 22 benefits due to restrictions.”

Oregon: The Fight Happening Right Now

Oregon has a bill working its way through the legislature. SB 1166 would establish minimum pay rates, require paid sick leave, and most importantly, require “just cause” for deactivations with appeal rights through arbitration or mediation.

The bill would also fund a $4 million Driver Resource Center and require companies to report deactivation data to the Bureau of Labor and Industries, data that doesn’t currently exist in any systematic way.

“Many of these workers drive more than 12 hours a day to pay their bills,” Senate Majority Leader Kayse Jama, the bill’s sponsor, said at a hearing. “They work sick because they have no other choice. They can lose their income at a moment’s notice with no way to tell their side of their story.”

Uber and Lyft oppose the bill. A Lyft representative testified that if it passes, ride prices would increase 33% and ride volume would decrease 25% or more. When a state senator asked if those calculations assumed the company would maintain its current profit margin, the representative said she couldn’t answer, which got laughter from supporters in the hearing.

The bill has been narrowed through amendments, and its fate is uncertain. But Drivers Union Oregon, which represents over 10,000 rideshare drivers in the state, is pushing hard.

Everywhere Else: The Void

And then there’s everywhere else. Texas. Florida. Georgia. Arizona. Pennsylvania. The entire South. The entire Midwest outside of Minnesota. Most of the Northeast outside of New York and Massachusetts.

In these states, gig workers have no specific statutory protection against arbitrary deactivation. None. If Uber decides tomorrow that you’re done, you’re done. Your options are to plead with customer service, hire a lawyer for an expensive and probably futile breach of contract claim, or… well, that’s basically it.

Some drivers have tried. On the UberPeople forum, one driver wrote about getting deactivated after 22,000 rides and a 5-star rating for 6 years.

“Lyft said a pax said I threatened to kill them,” he wrote. “I didn’t have a dash cam and Lyft said incidents… false accusations in 2016/2018 they decided to permanently deactivate me… it’s so unfair… in reality your next ride could be your last.”

Another responded: “It’s still the Wild West with these rideshare companies and the legalities that go along with deactivations. There are a lot of legal grey areas, and you can bet they have an army of lawyers that make sure they’re protected.”

The Wild West. That feels about right.

Meanwhile, in the Rest of the World

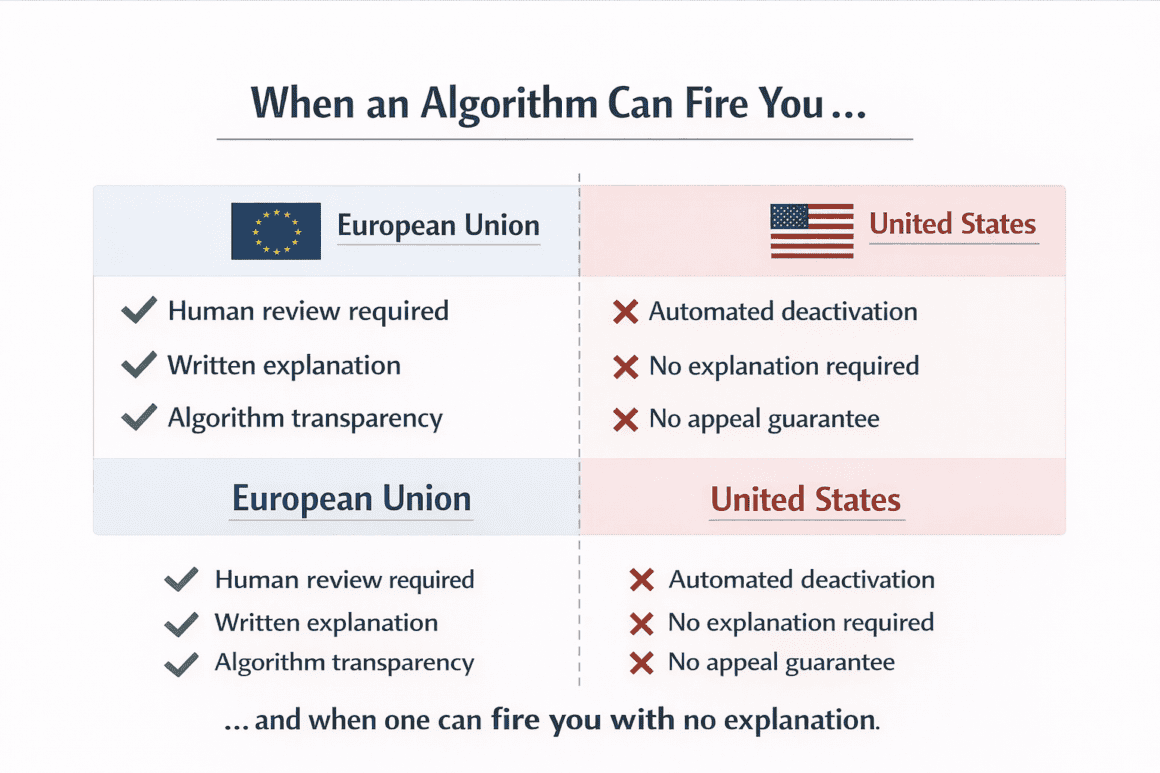

One thing that struck me while researching this: the United States is behind the rest of the developed world on this issue. Not surprising, maybe, but worth noting.

The European Union’s Platform Work Directive took effect on December 1, 2024. It requires that any decision to “restrict, suspend or terminate” a worker’s account must be made by a human being, not an algorithm. Companies must provide a written explanation “without undue delay.” Workers’ representatives get information about algorithmic decisions.

Member states have until December 2026 to implement it into national law. But the direction is clear: the EU thinks gig workers deserve basic protections against arbitrary firing. America, apparently, isn’t so sure.

“Gig workers live under the constant threat of being ‘deactivated’ (kicked off the app) and feel pressure to do unpaid work for clients who can threaten their livelihoods with one-star reviews,” the Electronic Frontier Foundation noted in analyzing the directive. “Workers also face automated de-activation: a whole host of ‘anti-fraud’ tripwires can see workers de-activated without appeal.”

The UK Supreme Court ruled in 2021 that Uber drivers are “workers,” not independent contractors, entitling them to minimum wage and holiday pay. Spain’s Supreme Court reached similar conclusions in 2020. Courts in the Netherlands have done the same.

American gig workers, by comparison, are mostly on their own.

What You Can Actually Do

So you’re a gig worker, and you’re worried about deactivation. Or you’ve already been deactivated. What can you do?

- If you’re in Seattle (app-based workers): You have real rights. Review your deactivation notice for the required elements. Request records substantiating the deactivation. Use the company’s internal challenge procedure. If that fails, file a complaint with the Office of Labor Standards.

- If you’re in Washington State (rideshare): Contact the Driver Resource Center operated by the Drivers Union. They can represent you in appeals.

- If you’re in New York City: The new law creates real protections. Contact the New York Taxi Workers Alliance. They’ve been fighting this fight for years and can help you navigate the new system.

- If you’re in Minnesota: You have a three-day notice and appeal rights. Document everything. Contact the Minnesota Uber/Lyft Drivers Association or file a complaint with the Department of Labor and Industry.

- If you’re in Colorado: Request a reconsideration meeting. Document any policy violations. You can file a civil suit for violations.

- If you’re somewhere without protections: Your options are limited, but not zero. Try the company’s internal appeal process, however frustrating. Document everything. See if the deactivation could be a discrimination claim, race, religion, national origin, or disability. Look into whether you might have been misclassified as an independent contractor. And consider connecting with driver organizations like Rideshare Drivers United or Gig Workers Rising to advocate for change.

One thing everyone can do: get a dashcam. Seriously. So many deactivation stories involve unverifiable customer complaints. If you have a video of what actually happened, you at least have evidence.

The Bigger Picture

I keep coming back to something Bhairavi Desai said: “For too long, Uber and Lyft have treated drivers as expendable.”

And that’s true. But it’s also true that laws can change.

Seattle proved that cities can pass strong deactivation protections. Washington State proved that statewide laws are possible. New York just passed the strongest just cause standard in the country. These things happened because drivers organized, because they showed up at city council meetings and state legislatures. After all, they refused to accept that this is just how things have to be.

“AALDEF’s report reflects the collective voice of drivers facing unjust firings by Uber and Lyft and shows that this is an industry-wide problem that needs an urgent solution,” Desai said when the October report came out. “This is a basic issue of economic stability and worker dignity.”

The gig economy isn’t going away. Millions of people depend on it for their livelihoods. The question is whether those people will have any say in how it treats them, or whether they’ll remain at the mercy of algorithms and unaccountable corporate decisions.

The answer, right now, depends entirely on where you live.

But it doesn’t have to stay that way.

Sources

- City of Seattle Office of Labor Standards, App-Based Worker Deactivation Rights Ordinance: https://www.seattle.gov/laborstandards/ordinances/app-based-worker-ordinances/app-based-worker-deactivation-rights-ordinance

- Washington State Department of Labor & Industries, Transportation Network Company Drivers’ Rights: https://lni.wa.gov/workers-rights/industry-specific-requirements/transportation-network-company-drivers-rights/

- Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry, New Statewide Minimum Compensation for TNC Drivers: https://www.dli.mn.gov/news/new-statewide-minimum-compensation-transportation-network-company-drivers

- Colorado General Assembly, SB24-075: https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/sb24-075

- Colorado General Assembly, HB24-1129: https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb24-1129

- Massachusetts Attorney General and Uber/Lyft Settlement Agreement: https://www.mass.gov/doc/attorney-general-and-uberlyft-settlement-agreement/download

- EU Council, Platform Work Directive: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/platform-work-eu/

- Minnesota House of Representatives Session Daily: https://www.house.mn.gov/sessiondaily/Story/18408

- AALDEF, Deactivated Without Cause Report: https://www.aaldef.org/press-release/aaldef-report-uber-and-lyft-deactivate-nyc-drivers-with-no-notice-no-due-process-and-no/

- Asian Law Caucus and Rideshare Drivers United, Fired by an App Report: https://www.asianlawcaucus.org/news-resources/guides-reports/fired-by-an-app-report

- National Employment Law Project, Why NYC Must Extend Just Cause Protections: https://www.nelp.org/why-nyc-must-extend-just-cause-protections-to-app-based-workers/

- Electronic Frontier Foundation, What Europe’s New Gig Work Law Means: https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2025/10/what-europes-new-gig-work-law-means-unions-and-technology

- Documented, “Majority Uber Lyft Drivers Deactivated Report AALDEF”: https://documentedny.com/2025/10/29/majority-uber-lyft-drivers-deactivated-report-aaldef/

- Documented, “Uber Lyft Deactivated Account Drivers Fight”: https://documentedny.com/2023/02/24/uber-lyft-deactivated-account-drivers-fight/

- CalMatters, “Prop 22 California Gig Work Law Upheld”: https://calmatters.org/economy/2024/07/prop-22-california-gig-work-law-upheld/

- CalMatters, “Gig Work California Prop 22 Enforcement”: https://calmatters.org/economy/2024/09/gig-work-california-prop-22-enforcement/

- Minnesota Reformer, “What’s in the Bill Regulating Uber and Lyft Driver Pay”: https://minnesotareformer.com/2024/05/21/heres-whats-in-the-bill-regulating-uber-and-lyft-driver-pay-and-labor-standards/

- Oregon Public Broadcasting, “Oregon Lawmakers Consider Rideshare Driver Protections”: https://www.opb.org/article/2025/04/29/oregon-lawmakers-consider-pay-bump-new-protections-for-rideshare-drivers/

- NW Labor Press, “Oregon: Stop Uber from Firing Us Without Cause”: https://nwlaborpress.org/2025/04/oregon-stop-uber-from-firing-us-without-cause/

- AutoMarketplace, “NYTWA Pushes Driver Deactivation Bill Through City Council”: https://automarketplace.substack.com/p/nytwa-pushes-driver-deactivation

- News India Times, “NYC Council Member Krishnan and NYTWA Celebrate Passing of Just Cause Protection Law”: https://newsindiatimes.com/nyc-council-member-krishnan-and-nytwa-celebrate-passing-of-just-cause-protection-law/

- Jacobin, “Local Wins for Gig Drivers Could Translate to National Gains”: https://jacobin.com/2024/07/gig-workers-drivers-union-gains

- TechCrunch, “Uber Takes Steps to Combat Unfair Driver Deactivations”: https://techcrunch.com/2023/11/13/uber-takes-steps-to-combat-unfair-driver-deactivations/

- Los Angeles Times (via AOL), “Uber and Lyft’s Deactivation Policy Is Dehumanizing and Unfair”: https://www.aol.com/news/column-uber-lyfts-deactivation-policy-181352409.html

- Boston DSA, “Opinion: MA AGO Settlement Does Not Go Far Enough”: https://bostondsa.org/2024/07/03/opinion-ma-ago-settlement-with-uber-lyft-does-not-go-far-enough/

- Fair Work Center, Deactivation Resources: https://www.fairworkcenter.org/legal-clinic/deactivation-resources/

- Drivers Union Washington: https://www.driversunionwa.org/

- New York Taxi Workers Alliance: https://www.nytwa.org/

- Rideshare Drivers United: https://www.drivers-united.org/

- Drivers Union Oregon: https://www.driversunionor.org/

- RideGuru, “Uber Deactivation for Safety Concerns”: https://ride.guru/lounge/p/uber-deactivation-for-safety-concerns

- UberPeople Forum, “Wrongful Deactivation Since Jan. 1, 2023”: https://www.uberpeople.net/threads/wrongful-deactivation-since-jan-1-2023.479735/

- The Rideshare Guy, “How To Appeal an Unfair Deactivation”: https://therideshareguy.com/fight-unfair-deactivation/